Last September, a slew of sexually explicit photos of female celebrities surfaced on the online forums Reddit and 4chan. The women photographed did not leak the photos, rather, they were stolen and published without their consent. This is revenge porn – and unfortunately this form of abuse is neither new nor uncommon.

Here’s what you need to know about revenge porn from this week’s guest blogger, Alexis Morse, a rising sophomore and student-activist at Occidental College.

So what is revenge porn?

Revenge porn is the posting, sharing, or publishing of nude and/or sexually explicit pictures/videos of a person on the internet without their consent, often accompanied by personal or identifying information. The name comes from the fact that perpetrators of revenge porn are often ex-partners or friends looking to get revenge by harming victims via the Internet and social media.

This goes back decades! In the 1980’s, the magazine Hustler started a section called Beaver Hunt, which consisted of user-submitted sexually explicit photos of women, often with information on the women like their sexual fantasies and their names. It turned out that many of these user submissions were sent in without the consent of the person being photographed, and Hustler was subject to multiple lawsuits as a result.

It is no surprise that non-consensual pornography has grown with the rise of social media. It is yet another consequence of cultural norms that trivialize, normalize, and condone sexual violence — otherwise known as rape culture. When rape culture exists, many people believe it is fair and okay to post, share or consume sexually explicit photos without someone’s consent. Even worse, it is so ubiquitous that it goes unnoticed. Ending revenge porn will involve legislative action, but also serious pushback against rape culture in our society.

Terrifyingly, perpetrators can now find many online outlets specifically for revenge porn where they can be shielded by the anonymity of the internet, and because social media is relatively new, there is not a collection of legislation regulating abuse in this form.

Is revenge porn sexual assault?

Revenge porn is digital sexual assault. Although it may not explicitly involve physical assault, it violates a person’s privacy, exposes them sexually, and brings immense harm to the victim. While photographs or videos may originally be privately shared or taken with the consent of the victim, the use of them later to violate a person’s privacy, safety or dignity is incredibly damaging.

Annmarie Chiarini was first made a victim of revenge porn in 2010. Her ex-boyfriend collected nude photos of her they had taken while in a relationship and put them up for auction on eBay, along with her name and the college where she taught. This launched Annmarie into years of distress. She suffered from PTSD, almost lost her job, and attempted suicide. The photos were even posted onto a porn website with a solicitation for sex and a title that would make it easy for her students to accidentally find the photos when Googling her. She says she called the police many times, consulted attorneys, and no one was able to help her. She either received an answer of “no crime was committed,” or “you shouldn’t have let him take those pictures of you.”

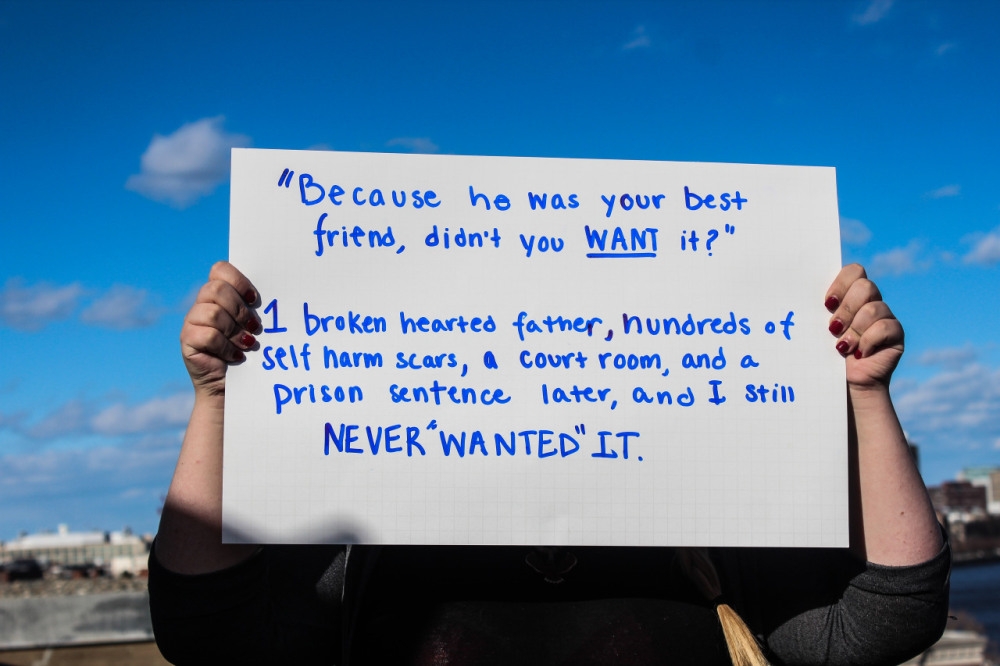

Her story displays the classic systemic and societal problems surrounding sexual assault. With revenge porn, the conversation is wrought with victim blaming (just don’t take naked pictures!), lack of legislation and protections, and incredible harm to the mental health, reputation, and lives of victims.

The lack of effort to stop revenge porn is yet another facet of rape culture. In a recent segment, John Oliver compiled a montage that demonstrates how most media discussion of revenge porn concludes that not taking sexually explicit pictures/video is the solution. This solution, put into context with any other crime, is absurd—if you didn’t want to be stolen from you shouldn’t have bought a house. The fact that victims are blamed for these actions is an extension of rape culture. People should be allowed to make decisions about what they do within their intimate relationships, and be protected if someone chooses to violate the terms of consent.

Is it illegal?

On a federal level, no—there is no law explicitly forbidding revenge porn, and only 24 states have revenge porn laws. In states without any revenge porn laws (and states with privacy laws that may apply, but no laws that apply explicitly to revenge porn), it can be almost impossible to get the photos/videos taken down, let alone prosecute the perpetrator.

Even with state laws, it is not enough to give victims full power to pursue their case and have the content removed entirely. Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act allows for sites that publish revenge porn to hide behind language that protects platforms from being punished for what users choose to do with that platform.

Recently, some companies have begun to take steps against revenge porn. In March of this year, Twitter changed its Terms of Service to explicitly ban “intimate photos or videos that were taken or distributed without the subject’s consent.” Even bigger, Google updated its search policy this month, allowing victims of revenge porn to submit a form to remove the website containing the revenge porn from Google’s search results. While this will not remove revenge porn from existence or help prosecute offenders, it will make revenge porn much harder to find and help protect victims from further harm in their personal and professional lives. However, it will take major federal action to give victims the full breadth of defense that these cyber assaults warrant.

Domestic violence and sexual assault are two of the most widespread problems in our communities.

Domestic violence and sexual assault are two of the most widespread problems in our communities.

A.D. Marrow is a writer living in North Carolina. Her new novel,

A.D. Marrow is a writer living in North Carolina. Her new novel,