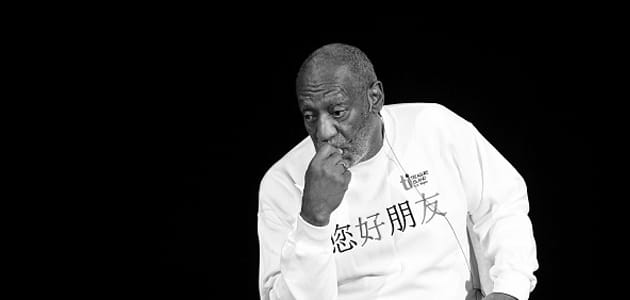

35 Women, #TheEmptyChair: Shedding Light on Bill Cosby & Why Sexual Assault Victims Are Not Believed

Bill Cosby is having a very bad week. On July 24th, prominent Washington Post columnist Ruth Marcus wrote an op-ed calling for President Obama to revoke Cosby’s Presidential Medal of Freedom. Taking issue with the President’s statement that there is no precedent for revoking the medal, Marcus urges Obama to follow in the footsteps of the U.S. Navy, which last year revoked Cosby’s honorary rank of chief petty officer. For his part, when asked about Cosby on July 15th, the President stated, “If you give a woman, or a man for that matter, a drug and then you have sex without their consent, that’s rape.”

In 2005, 14 women came forward and accused Cosby of rape after Andrea Constand, a former Temple University basketball star, pressed charges. In a deposition from that case, published earlier this month by the New York Times, Cosby admitted to preying on young women and using Quaaludes to get them to have sex with him. Still, the women who came forward at the time were largely met with skepticism and disbelief.

Barbara Bowman speaks to this in her account, “I felt like a prisoner; I felt I was kidnapped and hiding in plan sight […] who the hell would have believed me? Nobody, nobody.” And her fear of not being believed was a legitimate one – when she spoke to a lawyer soon after the alleged attacks, she was accused of lying. Her agent did nothing, either. Years later, Andrea Constand accused Cosby of rape and Bowman was asked to speak in court, but the case was quietly settled.

The accusers’ stories began getting traction in 2014, but only after comedian Hannibal Buress called Cosby a rapist in his stand-up routine, which went viral. This week, with their stories and photographs published together for the first time along with one empty chair, Cosby’s alleged victims and survivors everywhere are finally getting the attention and validation they deserve. As one of the women, the former model and actress Beverly Johnson, said in her testimony, “The part of it I wasn’t prepared for was the onslaught of women that have been assaulted and them telling me their story because I told mine.”

But there’s the #TheEmptyChair symbolizing the untold stories of real men and women who have also been sexually assaulted and suffered in silence, shame, and disbelief.

Why Accusations About Celebrities Aren’t Believed

Cosby isn’t the first icon to be accused of sexual assault or domestic violence, and yet the question persists: Why aren’t these accusers heard or given any credence—not just Cosby’s alleged victims, but the countless other men and women who have dared to challenge a celebrity?

The answer lies in the American conflation of celebrity and security, says Ulester Douglas, executive director of Men Stopping Violence. “We are a celebrity culture. Seeing someone we idolize, revere, and idealize being accused of horrific crimes makes us wonder: Who are we? It makes us realize that our own families could be capable of it, too,” he says. It’s unsettling and even terrifying to associate an idol with evil, particularly because there are so many celebrities who are good people, capable of powerful, positive influence.

Dissonance Perpetuates Silence

David Adams is a psychologist and co-director of Emerge, a Boston-based abusers’ intervention and counseling program. He sees a difference in how we respond to a stereotypical criminal and a celebrity accused of bad behavior due to our preconceptions about abusers, who can be male or female. “We tend to think of an abuser as someone who is easily detectable: someone who is crude, sexist, and boorish. A quarter of men who abuse women do fit this stereotype, and since that’s a substantial subgroup, we tend to spot those guys and not the ones who are more likable. If we don’t know what to do with bad information about someone we adore, it creates dissonance, and we sometimes choose to disbelieve or to ignore it,” he says.

“When we see someone likable accused of a crime, we have a choice to believe something bad about them or to discount it because it doesn’t fit our experience. In some ways it’s easier to do that than to think, oh God, the world really is unknowable—I might as well give up on knowing people,” he says. “If we don’t know what to do with information about someone we worship, we put it aside.”

Why Celebrities Feel Immune

Of course, Cosby is hardly the first famous person to be accused of rape or assault. When we think about any celebrity facing serious allegations, though, it’s difficult to believe that an image-conscious idol would be willing to engage in hugely risky behavior, throwing away the very image they need. What’s going through their mind?

“Any consequence is overridden by the high of the conquest,” Douglas says. And, on a purely logistical level, “They do it because they can. They truly think they can get away with it, based on the very fact that they have a certain image. They will be believed; the accusers will be laughed out of the room.”

Absorbing The Narcissism Factor

In many celebrity cases, narcissism also plays a starring role. “A hallmark of narcissism is exceptionality. You literally think you will not get caught. This personality takes chances, acts reckless, and even associates the behavior with success, because they’ve always been rewarded,” Adams says.

“We think narcissists are people nobody would like. But, in fact, they’re quite charismatic, with good social and image-maintenance skills”— which often allow them to get away with bad behavior, even more so when there’s a PR team on call. Narcissists are also skilled at compartmentalization, Adams says, and they choose to focus on the “part of their life that everybody adores. They don’t focus on other parts of their lives, and if they do something wrong, they think, ‘Gee, everybody loves me. What’s the problem?’” he says. “It’s a lack of character development.”

“Narcissists can engage in all sorts of psychological gymnastics not to feel empathy,” says Douglas.

The Changing Tide

Adams says that it’s easy to categorize personalities as good versus bad. “We don’t think good and evil can co-exist in the same person,” he says. “But look at the Mafia—these guys who do horrible things but are notoriously good to their mothers. And along comes a show like The Sopranos to paint them in a more nuanced light. There’s now less focus on ‘good guys’ and ‘bad guys,’” he says. Understanding the complexities of personalities—refusing to glorify a celebrity as all good, all the time—could help to close the dissonance gap.

“We can also go a long way toward preventing male sexual and domestic violence against women by stopping the pervasive and pernicious victim-blaming,” Douglas says. “The media, for example, should quit asking the toxic, ‘Why did you go back to your abuser?’ and ‘Why didn’t you leave?’ A reporter could say instead, ‘As you know, there are some who question your credibility because of some of the choices you made. What, if anything, would you want to say to them?’ That is respectful journalism. The [accuser] should never be made to feel like she has to justify the choices she made or makes.”

Finally, in his own work with Men Stopping Violence, Douglas sees firsthand the power of healing through sharing. “I see survivors who are finding peace through coming forward and telling their stories. One of the most powerful things that survivors can do is tell their own stories, on their own terms,” he says.

Portions of this post were originally published on November 19, 2014.

Together We Can End Domestic and Sexual Violence